“I was for ALEC before it was cool.” — Vice President Mike Pence [2]

[2] Bill Meierling, “Governor Mike Pence: ‘I was for ALEC before it was cool.’” ALEC Website, August 14, 2016, https://www.alec.org/article/governor-mike-pence-i-was-for-alec-before-it-was-cool/.

Introduction

Every year, hundreds of new laws in the United States are passed that emerge not from the needs or the will of the people, but rather from a shadow government composed of social conservatives and corporations seeking to advance their own interests. Behind closed doors, state and local lawmakers meet with conservative, right-wing activists and corporate executives (who pay tens of thousands of dollars for access), and together design model legislation that is then shipped out to state legislatures across the country and passed into law with alarming efficiency.

This co-opting of systems of governance by a private, unaccountable economic elite to advance their own agendas is an example of a phenomenon known as “corporate capture.” It is a deliberate strategy employed by corporations and those atop hierarchical systems of power and privilege to maintain the social, political, and economic status quo at the expense of human rights and ecological justice.

In other words, corporate capture is a weapon to use the political system to further oppress historically marginalized communities,. particularly when those communities demand a more just distribution of power and protection of the environment.

For more than 46 years, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) has refined the practice of corporate capture into a profitable and highly effective business model. Since 1973, the group has mastered the art of “pay-to-play” politics to provide an overwhelmingly powerful political platform that empowers not only the corporations that fund it, but also the groups that make up its ideologically conservative base.

By exploiting the power of its established networks, ALEC has developed a methodology that is efficient and effective: its corporate members propose or draft legislation in their own interest, and their legislative partners introduce those bills into their own legislative bodies. This happens several hundred times, producing several hundred new laws, in state legislatures across the country each year.[3]

[3] See: “Legislative Membership,”American Legislative Exchange Council website, https://www.alec.org/membership-type/legislative-membership/; see also Hertel-Fernandez, at 48 and 72. In its 2000 annual report, ALEC claimed that it introduced 3,100 pieces of legislation in the 1999-2000 legislative cycle, 450 of which became law. See Hertel-Fernandez, 48.

ALEC has drawn criticism from anti-corruption and watchdog organizations for designing laws behind closed doors without any input from the public. ALEC-affiliated legislators have similarly drawn criticism for introducing legislation into their legislative bodies lifted verbatim from ALEC documents.[4]

[4] For example, see Minnesota House debate from April 25, 2012, where Representative Atkins confronts Representative Gottwalt over Representative Gottwalt’s use of ALEC-branded legislative materials when introducing a healthcare bill (SF 1933). See here: https://youtu.be/6kX7JGcQk2I at 2.22.22-2.24.59.

However, ALEC’s material danger to communities under threat reaches far beyond the anti-democratic processes through which ALEC drives legislation. People of color are also disproportionately affected by the goals and impacts of much of the legislation ALEC pushes for. ALEC is specifically devoted to expeditiously spreading racist ideas and corporate agendas across the country that target the rights and lives of communities of color.

This section briefly traces the development of the ALEC platform from its founding as a vehicle for politicizing evangelical doctrine and dogma, to its growth as a modern incubator for codifying corporate power. While adding corporate membership to ALEC was born of necessity — funding only the policies that energized evangelical conservative groups proved unsustainable by the early 1990s[5] — the comfortable corporate-conservative alliance reveals the fundamentally illiberal underbelly of corporate capture. Although their individual policy priorities are not necessarily in perfect alignment, both corporations and social conservatives share an interest in defending a status quo that enables and is built upon the extraction of profit at an unending human and ecological cost.

[5] By 1988 ALEC was in dire financial circumstances with $2 million of unfunded liabilities. See: Hertel-Fernandez, 39.

Curbing Social Change: A Brief History of ALEC

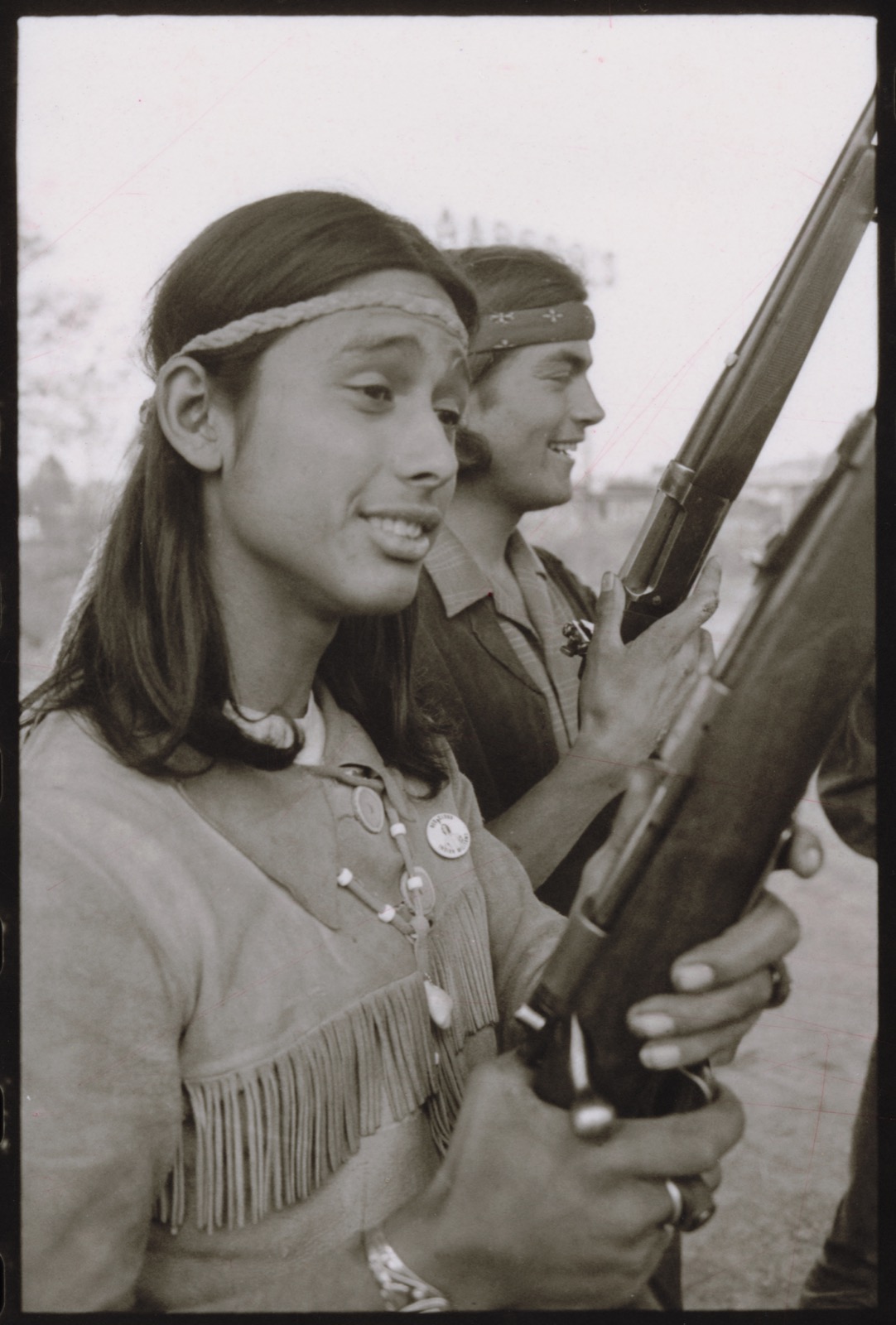

The second half of the 20th century saw a socio-political revolution in the United States. Social movements across the country challenged dominant power structures that privileged a small, powerful elite class of primarily heterosexual, white, wealthy men, while subjugating everyone else. The Civil Rights and Black Nationalist movements demonstrated immense people power against a white supremacist society; the formation of the American Indian Movement, or AIM, represented a new incarnation of the centuries-long fight against settler colonialism; a new feminist movement emerged, demanding gender equality; the struggle for queer and trans liberation challenged the heteronormative patriarchy; and the modern environmental movement demanded decisive action on pollution to protect our air, land, and water. Similar progressive forces brought forth significant political change in other countries, including the decades-long social movements that successfully overturned military regimes in Latin America and colonial regimes across Asia and Africa. Among all these struggles, the fights against apartheid in South African and settler colonialism in occupied Palestine garnered enormous international attention.

As has been the case throughout history, these progressive shifts in society and politics were met with a swift backlash from the dominant elite determined to maintain the status quo.

The staunchly right-wing American Christian evangelical movement was particularly resistant to egalitarian social change. After the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited racial segregation in education in 1954, fundamentalist Christians reacted feverishly to, in their view, “protect” their children by enrolling them in all-white, private evangelical “segregation academies.”[6] A tipping point came in 1971, when the federal government dealt a potentially fatal blow to segregated education by revoking tax-exempt status from private schools without a non-discrimination policy.”[7] Prominent American evangelical pastor Jerry Falwell famously complained: “In some states it’s easier to open a massage parlor than to open a Christian school.”[8]

[6] Ibid, 303.

[7] Internal Revenue Service, Revenue Ruling 71-447, 1971, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-tege/rr71-447.pdf.

[8] Max Blumenthal, “Agent of Intolerance,” The Nation, May 16, 2007, https://www.thenation.com/article/agent-intolerance/.

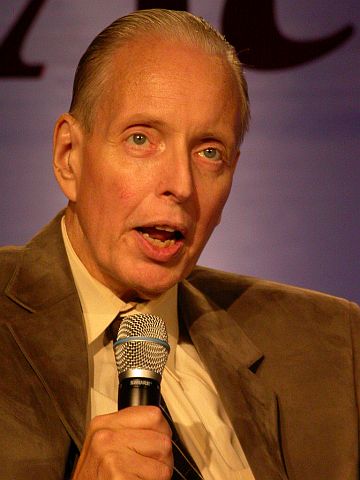

Closely following this development was Paul Weyrich, a dedicated conservative Evangelical Christian and aspiring political activist who was already interested in building a politicized American conservative evangelical movement. In the years prior, Weyrich had tried to rally American evangelicals around a number of conservative social causes, including against pornography, for prayer in schools, and against gender equality. But, by his own account, those efforts “utterly failed.”[9][10]

[9] Randall Balmer, “The Real Origins of the Religious Right,” Politico, May 27, 2014, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/05/religious-right-real-origins-107133.

[10] Randall Balmer, Thy Kingdom Come: How the Religious Right Distorts Faith and Threatens America (New York: Basic Books, 2007), 15.

In response to the creeping social change brought on by progressive political movements, most recently in forced racial integration, and to advance his staunchly conservative evangelical political values, Weyrich founded a number of right-wing political organizations. He soon found that the restrictions on segregated education marked a critical change in his community; his evangelical peers were finally as eager as he was to fight back against social progress.

At that moment, Weyrich energized a newly politicized conservative evangelical base by opening its eyes to its ability to reclaim power and roll back civil rights gains through the political process.

One of the organizations Weyrich founded at that time, specifically to work behind the scenes in state legislatures, was the American Legislative Exchange Council. Weyrich left no doubt that his intention in founding ALEC and similar groups was to overturn the progressing sociopolitical order. What he and others were doing was “different from previous generations of conservatives,” he told an audience. “We are no longer working to preserve the status quo. We are radicals, working to overturn the present power structure of this country.” [11] He later elaborated on his fundamentalist counter-revolutionary philosophy to his long-time conservative evangelical associate, Richard Viguerie, that what he was engaged in was war. He said, “it may not be with bullets, and it may not be with rockets and missiles, but it is a war, nonetheless. It is a war of ideology, it’s a war of ideas, it’s a war about our way of life. And it has to be fought with the same intensity, I think, and dedication as you would fight a shooting war.”[12a] Such was Weyrich’s zeal that when former House Speaker Newt Gingrich reflected on the history of modern conservatism, he noted “no single person other than Ronald Reagan has done more to create the modern conservative movement than Paul Weyrich."[12b]

[11] David Grann, “Robespierre Of The Right,” The New Republic, October 27, 1997, https://newrepublic.com/article/61338/robespierre-the-right.

[12a] Richard Viguerie, The New Right: We’re Ready to Lead (Falls Church, VA: The Viguerie Company, 1981), 55.

[12b] Richard Viguerie, Alf Tomas Tonnessen, How Two Political Entrepreneurs Helped Create the American Conservative Movement, 1973-1981: The Ideas of Richard Viguerie and Paul Weyrich (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2009)

But Weyrich ‘s and his community’s fanaticism — and the flush of funding he received from billionaire allies at the outset — was not enough to sustain an organization with such an ambitious agenda forever. Almost twenty years after its founding, ALEC found itself in a funding crisis, with $2 million of unfunded liabilities.[13] The situation was dire: in 1996, a board member worried that ALEC “will go under if there is not a significant influx of money in a short period of time”.[14]

[13] Hertel-Fernandez, 39.

[14] American Legislative Exchange Council, Joint Board of Director Meetings, May 30, 1996,

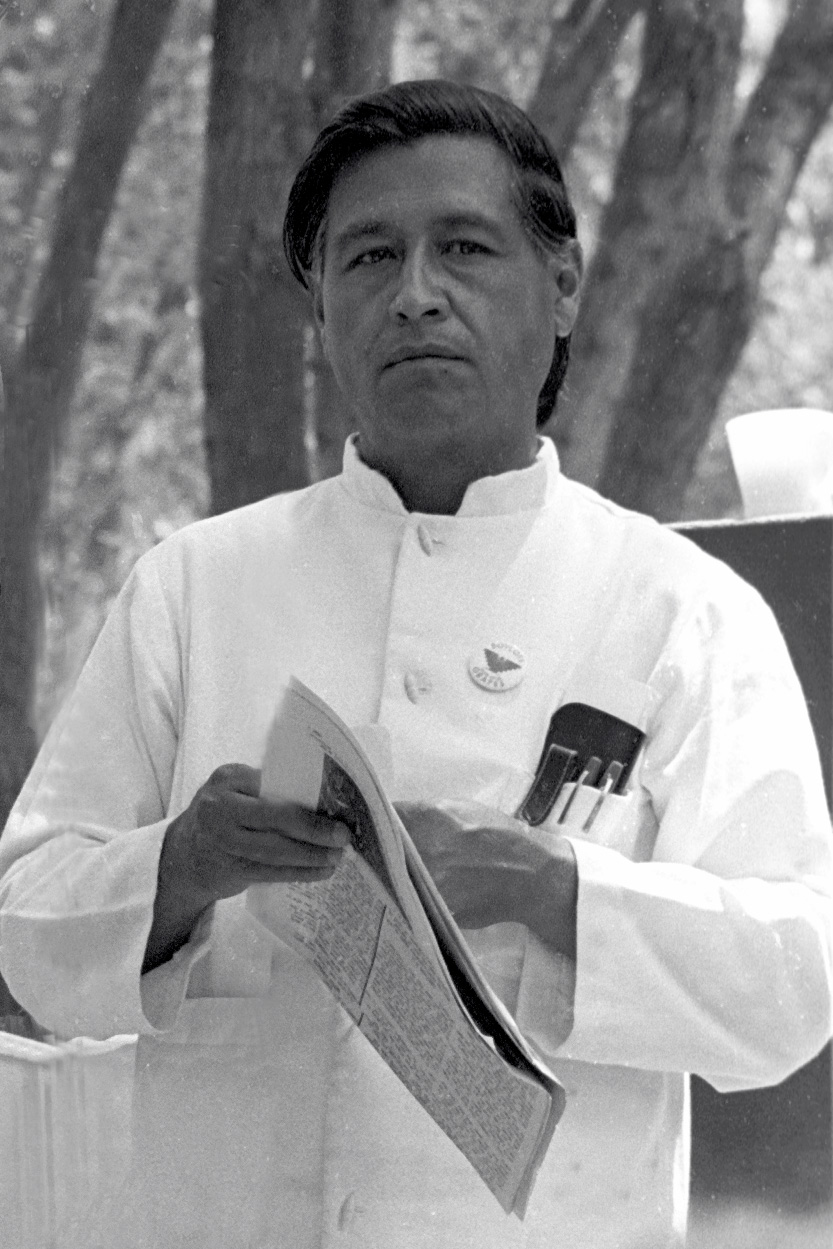

While Weyrich and his evangelical peers fought social and racial progress tooth and nail, corporate America faced similar challenges to capitalist orthodoxies. In the early second half of the 20th century, American capitalism faced unprecedented critiques at home from communities protesting the exploitation of laborers and consumers and the racial injustices it compounded. While grassroots movements like the Latinx and immigrant farm workers led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta challenged the corporate exploitation of laborers, a new movement of lawyers and consumer activists demanded corporate accountability and decried the impacts of corporate deregulation on consumers and the broader public.[15]

[15] Drutman, 55.

Like their evangelical counterparts, corporate executives across the country feared the end of their unchecked dominance. A particularly alarmist group of devout capitalists formed the “League to Save Carthage,” an association of corporate executives who believed the U.S. was on an inexorable slide toward socialism. [16]

[16] Jane Mayer, Dark Money: The Hidden History of the Billionaires Behind the Rise of the Radical Right (Anchor Books: New York, 2016), 74.

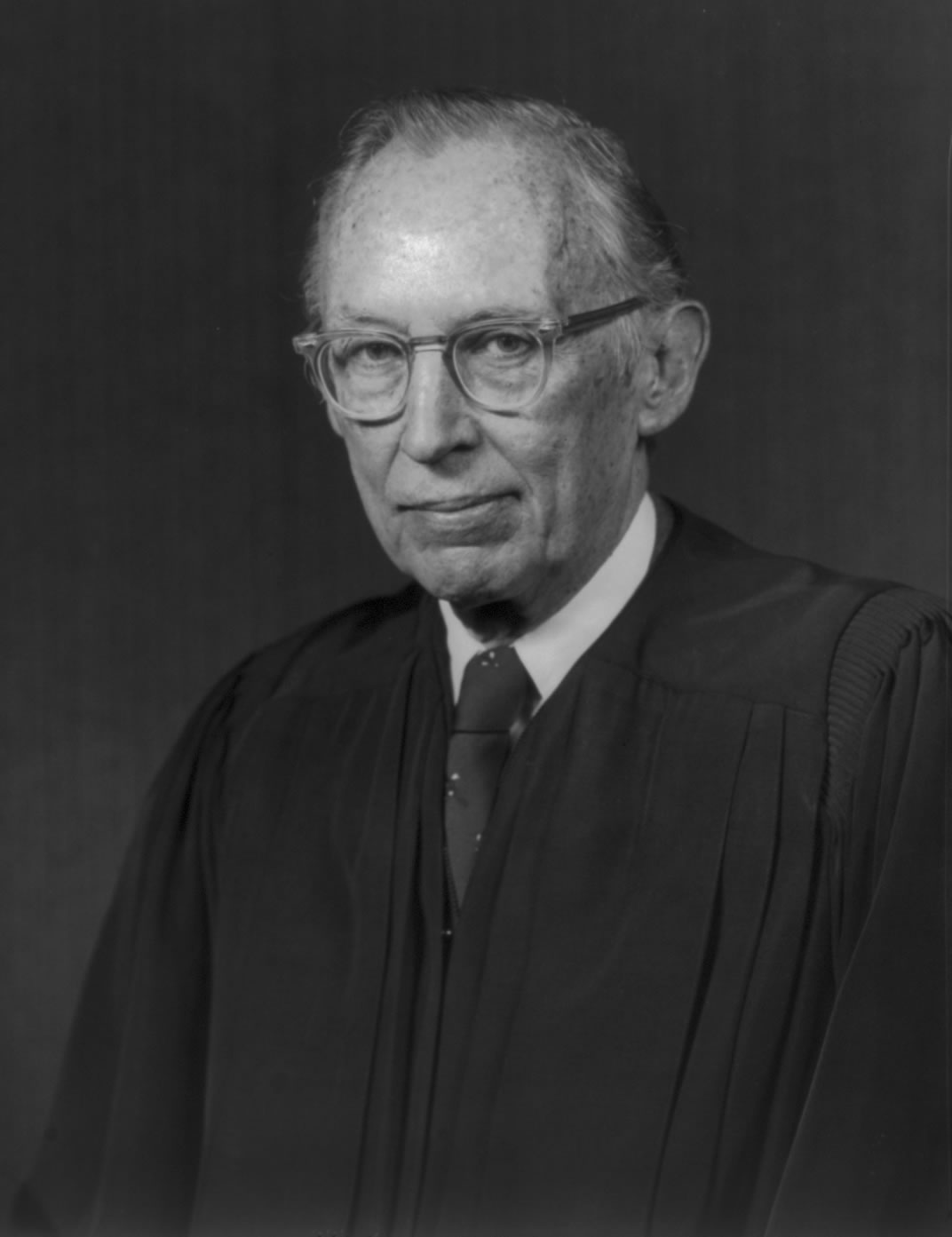

One member of the League to Save Carthage, Lewis F. Powell, drafted a highly influential and now-infamous, staunchly pro-corporate memo to the Director of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in 1971 that channeled the panic spreading through corporate America.[17] Powell issued a call for American businesses to more assertively influence all sectors of political and social life. In other words, to politicize themselves in the same way that Weyrich had been urging evangelicals to do. According to the Powell memo, at stake was nothing less than “survival — survival of what we call the free enterprise system, and all that this means for the strength and prosperity of America and the freedom of our people.”[18] The memo made plain that “businesses must learn the lesson … that political power is necessary.”[19]

[17] Mayer, Dark Money, 89.

[18] Ibid, 10.

[19] Ibid, 10.

The message was well-received.[20] Corporate America no longer feared government, but instead saw in it a major opportunity to expand their reach in American political life. Corporations no longer had to play defense; by entering what Powell called the “neglected political arena,” they could take the offensive. This was their wake-up call.

[20]Ibid, 24.

A lucrative new lobbying industry emerged. Over the course of the 1970s, the number of companies with a registered lobbyist presence in Washington, D.C. grew from 175 to 2,445. Corporations increasingly waded into electoral politics, as well: in the second half of the 1970s, the number of companies with political action committees quadrupled. By the end of the decade, four out of five Fortune 500 companies had an “External Relations” department, considered a “rarity” just years earlier. [21]

[21] Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson, Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer and Turned Its Back On The Middle Class (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 118.

Perfectly positioned to service the growing group of newly politicized corporate executives was a cash-strapped influential evangelical Christian organization in search of a viable economic model to sustain itself. ALEC identified a lucrative opportunity to stay afloat by harnessing corporate funding. A report prepared for its leadership outlined a suggested approach. Specifically, the report argued that “ALEC must begin to function more like a business, and recognize that it has a product that it provides to a defined customer base for a ‘profit.’ In other words, there can be no mission without margin.”[22a] It continued, “ALEC’s product is policy, and its customers are state legislators and private sector supporters.”[22b]

[22a] American Legislative Exchange Council, Meeting the CHallenge: Ideas + Action = Results. A Business Plan for the American Legislative Exchange Council, 2, https://www.industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=slgp0088

[22b] Ibid.

“ALEC’s product is policy, and its customers are state legislators and private sector supporters.”

And where ALEC saw a new and much needed revenue stream, corporate executives across the country saw an untapped network of political influence to roll back the threat that Powell so desperately warned of.

ALEC revamped its operations to appeal to corporations willing to pay for access. Most notably, it placed a new emphasis on its Task Forces, the groups that bring together corporations and lawmakers to draft model laws. ALEC knew, from the memo provided to leadership, that charging a sizable membership fee to the Task Forces, would prove to be its financial savior.

With a shift in ALEC’s business model, its fundamental mission necessarily changed in tandem. Recent data compiled by Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Assistant Professor in Columbia University's School of International and Public Affairs, shows that in the ensuing years, ALEC increasingly prioritized corporate-driven legislation over the conservative social agenda espoused by its founders. Whereas as much as 20 percent of ALEC model legislation between 1977 and 1979 related to “social issues” such as abortion and religious freedom, only four percent of ALEC model legislation in this timeframe concerned business regulation issues. In the following years, corporations pulled ALEC’s focus toward deregulation and corporate profit. By 1993 to 1995, nearly 50 percent of ALEC model legislation was advancing ALEC members’ pro-business agenda, while model legislation related to social issues had dropped to just two percent.[23]

[23] Hertel-Fernandez, 37.

The group’s focus had swung back somewhat by the early 2000s, and the back-and-forth continues today, as ALEC’s conservative and pro-corporate members share its platform to draft and push through legislation to advance their own interests, twisting and corrupting state-level democratic lawmaking processes to serve their own ends.

The alliance is a natural one: corporate and political elites are two sides of the same proverbial political ‘coin’. Capitalist profiteering depends on an exploitative economic system that is based on racial subjugation, and conservative political elites rely on disenfranchising racial minorities to hold on to political power. Each of these branches of white supremacist power — economic and political — serve each other’s interests through entities like ALEC that capture and privatize economic and political power at the expense of historically marginalized people. Though white supremacist political and economic power manifest differently in different policy priorities, both thrive by targeting the human rights and self-governance of communities of color.

The People's Resistance to ALEC

ALEC finally came under significant scrutiny by mainstream American progressive organizations following a pivotal event in American politics in 2012: the murder of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager killed by a man named George Zimmerman in a gated Florida community. Zimmerman, who fatally shot the teen, was not arrested or charged with a crime for 45 days.[24]

[24] Edward B. Colby, Brian Hamacher, and Lisa Orkin Emmanuel, “George Zimmerman Charged With Second-Degree Murder,” NBC News, April 11, 2012, https://www.nbcmiami.com/news/George-Zimmerman-Not-a-Flight-Risk-Former-Attorney-146966625.html.

When he was finally brought into the criminal justice system, commentators widely doubted that prosecutors could convict him of murder, due to an arcane statute passed seven years earlier. The now-infamous “Stand Your Ground” law eliminates the “duty to retreat,” effectively providing legal cover to murder when the would-be defendant murderer feels that their life is in dagner (regardless of whether it actually is).[25]

[25] Eyder Peralta, “Trayvon Martin Killing Puts 'Stand Your Ground' Law In Spotlight,” National Public Radio, March 19, 2012, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2012/03/19/148937626/trayvon-martin-killing-puts-stand-your-ground-law-in-spotlight.

When the public learned more about the Stand Your Ground law, interest grew in the origins of the legislation. Soon enough, guided by existing advocacy campaigns, organizers and the general public turned their eyes to the group behind the law

Several advocacy groups, led by Color of Change, already had their sights set on ALEC in response to its behind-the-scenes work passing Voter ID laws leading up to the 2012 election.[26] In a 2011 report, the NAACP singled out ALEC as a source of model voter ID legislation intended to disenfranchise minority voters.[27] Also that year, the Center for Media and Democracy, having obtained copies of over 800 bills from an internal whistleblower, launched ALEC Exposed, a website that publishes, analyzes, and tracks ALEC-affiliated bills. A coalition of these groups, including Color of Change and the Center for Media and Democracy, also launched a public campaign targeting ALEC and its members with petitions, rallies, and private outreach. The campaign notably included a call to boycott corporate sponsors and affiliates of ALEC.[28]

[26] Center for Media and Democracy, “Color of Change Targets ALEC Corporations,” PR Watch, December 15, 2011, https://www.prwatch.org/news/2011/12/11186/color-change-targets-alec-corporations.

[27] NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, “Defending Democracy: Confronting Modern Barriers to Voting Rights in America,” 2011, https://www.naacpldf.org/wp-content/uploads/Defending-Democracy-12-16-11.pdf.

[28] Color of Change, “Targeting and Weakening ALEC,” https://colorofchange.org/campaigns/victories/targeting-and-weakening-alec/.

But following the murder of Trayvon Martin, racial justice advocates caught a glimpse of the wide-reaching impacts of ALEC’s work on communities of color. The boycott campaign against ALEC exploded in size and in impact, as more and more progressive groups joined in. Facing pressure from Color of Change and a grassroots coalition of racial justice activists, a number of companies, including Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, Mars Inc., Wendy's, McDonalds, the Gates Foundation, Kraft, Walgreens, and even Walmart ended their long-standing ALEC memberships.[29] Although the companies did not mention ALEC by name, a statement released by ALEC just days after losing many corporate sponsors confirms the success of the boycott, or what it called an “intimidation campaign.”[30]

[29] Hertel-Fernandez, 59; Peter Overby, “Boycotts Hitting Group Behind 'Stand Your Ground’,” National Public Radio, April 5, 2012,

[30] American Legislative Exchange Council, “Statement by ALEC in Response to the Outpouring of Support in Wake of Intimidation Campaign Against Its Members,” ALEC press release, April 12, 2012,

As ALEC kept losing different funding sources each week, attracting more negative press than it ever had in its forty-year history, the group sought to stem the tide of losses by publicly dissolving the ALEC “Public Safety and Elections Task Force” which was responsible for promoting both voter ID laws and “Stand Your Ground” laws.[31] ALEC refused to admit that the decision to eliminate the task force was due to pressure from the boycott and targeted advocacy, insisting instead that they were “...redoubling [their] efforts on the economic front, a priority that has been the hallmark of [the] organization for decades.”[32]

[31] Eric Lichtblau, “Martin Death Spurs Group to Readjust Policy Focus,” New York Times, April 17, 2012, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/18/us/trayvon-martin-death-spurs-group-to-readjust-policy-focus.html; Adam Sorensen, “ALEC Scraps Gun-Law, Voter-ID Task Force,” Time, April 17, 2012,

[32] American Legislative Exchange Council, “ALEC Sharpens Focus on Jobs, Free Markets and Growth — Announces the End of the Task Force that Dealt with Non-Economic Issues,” ALEC press release, April 17, 2012,

At the same time, ALEC implemented superficial policy changes internally to deflect criticism of undue corporate influence. After spring 2013, only legislator members of ALEC — and no longer lobbyists — could introduce legislation at ALEC convenings.[33] However, documents made public in a lawsuit filed by the Center for Media and Democracy revealed that the change was “just a sham” and corporate members still led the internal policy proposal process.[34]

[33] Common Cause and the Center for Media and Democracy, joint letter to IRS, May 12, 2015, https://www.commoncause.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/policy-and-litigation/letters-to-government-officials/joint-letter-to-irs-alec-tax-status.pdf.

[34] Ibid.

By 2013, following the boycott, advocacy campaign, and decision to end the Task Force, ALEC saw more than 100 corporations and 400 state legislators formally sever affiliations.[35] With declining membership, the group’s budget was dealt a significant blow: at the end of the year, ALEC found itself with a $1.2 million budget deficit.[36]

[35] Color of Change, “Targeting and Weakening ALEC,” https://colorofchange.org/campaigns/victories/targeting-and-weakening-alec/

[36] Ibid.

In its 2016-2018 strategic plan, ALEC confirmed the success of the boycott, acknowledging what it euphemistically called a “difficult period”: “Given its effectiveness, ALEC is closely scrutinized by the Left and has faced especially harsh attacks from those opposed to free-market policy in the past few years. This caused some upheaval in the organization’s funding base, as many corporate members and sponsors broke off to avoid controversy….”[37]

[37] American Legislative Exchange Council, Strategic Plan: 2016-2018, 8, https://www.alec.org/app/uploads/2016/06/ALEC-Strat-Plan-Final-051616.pdf

Another form of resistance ALEC has faced since the groundswell of attention it attracted in 2012 has come in the form of litigation, largely led by a pro-transparency and pro-democracy organization called Common Cause. In April 2012, in the midst of the boycott and aftermath of Trayvon Martin’s murder, Common Cause filed a whistleblower complaint against ALEC, accusing the organization of commiting wide-reaching tax fraud. The complaint alleges that ALEC has misrepresented itself to the federal government and has underreported its lobbying activities in order to maintain tax-exempt status.[38]

[38] Common Cause, ALEC Whistleblower Complaint, webpage, October 1, 2016, https://www.commoncause.org/resource/alec-whistleblower-complaint/.

Although the watchdog group has filed three supplemental submissions to the IRS substantiating their claims against ALEC, and a former head of the IRS division in charge of overseeing non-profit and exempt organizations filed a separate complaint on behalf of a group of clergy called Clergy VOICE, the IRS has taken no public action to date.[39] And although ALEC has not commented publicly on the litigation, in spring 2013, it set up an affiliated shadow organization under the IRS 501(c)(4) classification, called the Jeffersonian Project, to conduct the kind of direct political lobbying that ALEC, as a 501(c)(3), cannot.[40] Although ALEC maintains that it does not conduct political lobbying and is therefore entitled to tax-exempt status, it acknowledged in the internal memo updating its members on the creation of the Jeffersonian Project that “[a]lthough [they] do not believe any activity carried on by ALEC is lobbying, the IRS could disagree. If that is the case, it would be possible to resolve any such issue with the IRS by agreeing to transfer the activity in question from ALEC to the Jeffersonian Project.”[41]

[39] John Dubnar, “ALEC Faces New Challenge to Tax-Exempt Status,” Center for Public Integrity, July 2, 2012, https://publicintegrity.org/federal-politics/alec-faces-new-challenge-to-tax-exempt-status/.

[40] Common Cause and the Center for Media and Democracy, joint letter to IRS, May 12, 2015, https://www.commoncause.org/wp-content/uploads/legacy/policy-and-litigation/letters-to-government-officials/joint-letter-to-irs-alec-tax-status.pdf.

[41] American Legislative Exchange Council, “Board/PEAC Committee Meetings,” August 6, 2013, 13,

At the same time, a coalition of organizations, including Common Cause and others, has continued appealing directly to corporations to cut their ties with ALEC[42] and has published a detailed report each year since 2011 exposing ALEC’s influence in the state where it decides to hold its annual conference.[43] Similarly, a coalition of groups has formed another pressure group called Stand Up to ALEC[44] to encourage constituents to pressure their representatives to cut ties with ALEC.[45]

[42] https://www.commoncause.org/resource/coalition-letters-to-alec-corporate-funders/.

[43] Jay Riestenberg, Common Cause, “Coalition Letters to ALEC Corporate Funders,“ August 26, 2018,

[44] Alliance for Retired Americans, “Stand up to the American Legislative Exchange Council and Protect Pensions,” March 14, 2014, https://retiredamericans.org/stand-up-to-the-american-legislative-exchange-council-and-protect-pensions/.

[45] Stand Up to ALEC, homepage, https://standuptoalec.org/.

ALEC will continue to attract criticism and attention so long as it continues to advocate for laws that undermine the social, economic, and political protections people rely on, particularly people of color. Aside from the “Stand Your Ground,” voter ID, anti-Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS), and critical infrastructure laws covered in this report, there are many examples of how ALEC has tried, often successfully, to pass regressive laws that have a distinctly negative impact on people of color. ALEC played a role in bringing about SB 1070 – the infamous Arizona law that made it a state misdemeanor crime for an alien to be in Arizona without carrying the required documents. The law effectively granted authority for law enforcement to racially profiling Latinx people, since it exclusively targeted undocumented people, for the benefit of ALEC members operating privately-run immigration detention centers.[46]

[46] Beau Hodai, “Corporate Con Game,” In These Times, June 21, 2010, http://inthesetimes.com/article/6084/corporate_con_game/.

ALEC also supported its private prison industry members to promulgate laws that increased this industry’s profits, such as “three strikes” and “truth in sentencing” laws, as well as laws developed by its members in the bail bond industry that privatize the parole process.[47] All of these laws disproportionately impact communities of color.

[47] Mike Elk and Bob Sloan, “The Hidden History of ALEC and Prison Labor,” The Nation, August 1, 2011, https://www.thenation.com/article/hidden-history-alec-and-prison-labor/.

ALEC has also played a central role in the design and development of the deliberately misnamed “Right to Work” laws that do nothing to guarantee employment but instead directly undermine the viability of unions. These laws prevent unions from negotiating contract provisions that require workers to contribute to the costs of worker representation on the job. Right to Work laws depress wages for Black and brown workers compared with non-Right to Work states.[48]

[48] Valerie Wilson and Julia Wolfe, “Black workers in right-to-work (RTW) states tend to have lower wages than in Missouri and other non-RTW states,” Economic Policy Institute, May 15, 2018, https://www.epi.org/publication/black-workers-in-right-to-work-rtw-states-tend-to-have-lower-wages-than-in-missouri-and-other-non-rtw-states/.

ALEC has long actively denied that the climate crisis,[49] which people of color are disproportionately impacted by, is caused by carbon emissions resulting from human activity.[50] ALEC wrote in a 2011 submission to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that “carbon dioxide is a naturally occurring, non-toxic and beneficial gas, and it poses no direct threat to public health. In order to justify regulation, the EPA is relying on an uncertain assumption that increased carbon dioxide emissions by humans are causing an unprecedented global temperature increase.”[51]

[49] ALEC & Climate Change Denial, homepage, http://alecclimatechangedenial.org/.

[50] American Public Health Association, “An Introduction to Climate Change, Health, and Equity: A Guide for Local Health Departments,” Climate Health Connect, http://climatehealthconnect.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Guide_Overview.pdf, p.3.

[51] American Legislative Exchange Council, Submission to the Environmental Protection Agency, “Re: Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions for New Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units,” 2011, https://web.archive.org/web/20120701002053/http://www.alec.org/wp-content/uploads/Comment_ALEC_Docket-ID_No.-EPA-HQ-OAR-2011-0660.pdf.

While these ALEC efforts, and many others not covered in this report such as its attacks on reproductive rights,[52] have contributed to the rightward shift in law and politics, ALEC’s attacks on the planet, people of color, and other historically marginalized communities are inadvertently adding strength to the growing cross-movement resistance to ALEC’s efforts. What the legacy of resistance that Center for Media and Democracy, Common Cause, Color of Change and others have shown is that when people of conscience organize and resist, ALEC is weakened. This history provides the path on which a new generation of activists is building.

[52] Wisconsin House Representative, Chris Taylor “The Attack on Planned Parenthood,” Truthout, July 31, 2015, https://truthout.org/articles/the-attack-on-planned-parenthood-a-view-from-inside-alec/.